How to read the outputs of Didgelab

When reading the outputs of Didgelab, you will ask yourself many questions, such as “why would I care for the tuning of a didgeridoo?” or “what the heck is impedance?” This article wants to explain the most important concepts one by one. The article is not about Didgeridoo physics. If you want to learn about Didgeridoo physics, I advise to watch the videos of Andrea Ferroni (e.g., this and this). This article explains the following concepts:

Toots

Each didgeridoo has a series of toots. When we talk about the tuning of the didgeridoo, we mean the toots. Each toot has a frequency, e.g., 146 Hz, which is also a note (146 Hz is D2). From the physics point of view, there is no difference between the ground tone and a toot. Generally, the ground tone or base frequency is the lowest toot.

Impedance

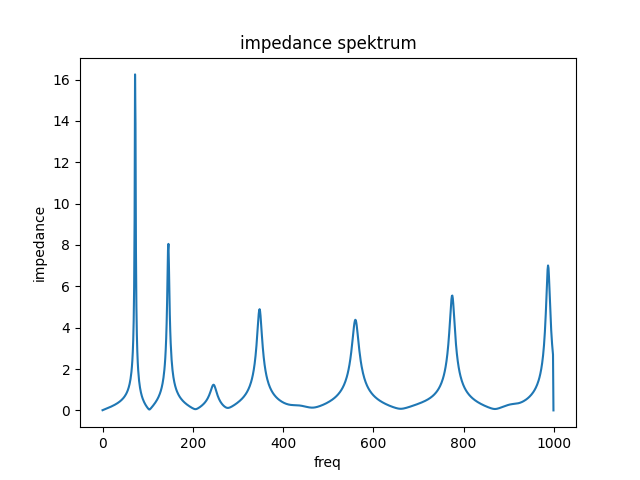

Impedance denotes how strong the didgeridoo reacts if you play it in a certain frequency. The impedance is different for each frequency. The impedance spectrum is a chart with frequency on the horizontal and impedance on the vertical axis. Here is an example of the impedance spectrum of the Arusha didgeridoo.

When you play the didgeridoo, your lips produce a soundwave at a certain frequency. When playing the ground tone, you feel a very strong response from the didge. Lets call this the response the resonance. The resonance is super high at the ground tone. If you bend the tone a little up or down, you have less resonance and, very quickly, the resonance breaks down completely and you cannot play it at all. This is because the didgeridoo has a resonant peak in the impedance spektrum at the ground tone. The impedance describes how much resonance a didgeridoo produces at a certain frequency. Resonance is still high a few Hertz away from the ground tone frequency, so you can bend the tone a bit. A few Hertz further, the tone breaks down completely because the impedance of the didgeridoo is too low. The next note that you can play is the first toot, which is the next peak in the impedance spektrum. Each toot of the didgeridoo is a peak in the impedance spektrum. Vise-versa, you can read the toots of a didgeridoo from the impedance spektrum. The height of each toot denotes how “playable” a toot is. The higher the peak, the easier the toot is to play.

The impedance spektrum (and, similarly, the sound spektrum) reach only from 1-1000 Hz only. The human ear can perceive sounds from 1-20.000 Hz. The interesting frequencies in the didgeridoo are generally below 1000 Hz and, therefore, we show only these freuqencies.

Resonant frequencies table

Another way to read the impedance chart is the “resonant frequencies table”. It shows all peaks (or maxima) from the impedance spektrum of a didgeridoo. Here is the resonant frequencies table to above impedance spektrum.

freq impedance rel_imp note-number cent-diff note-name

73.4 2.17e+07 1.00 -31 0.38 D1

147.0 8.88e+06 0.41 -19 -1.98 D2

220.0 1.17e+07 0.54 -12 0.00 A3

349.0 4.37e+05 0.02 -4 1.13 F3

440.0 1.67e+07 0.77 0 0.00 A4

695.0 5.79e+06 0.27 8 8.59 F4

988.0 1.66e+06 0.08 14 -0.41 B5

Here is an explanation of the columns of the table

- freq is the frequency of the resonant peak.

- impedance is the impedance of the resonant peak. The impedance is a rather large number and, therefore, written in scientific notation. It is not very usable in this format.

- rel_imp is the relative impedance, which is the impedance divided by the first impedance. The relative impedance of the first peak is, of course, always 1. In this example, the relative impedance of the 2nd peak is 0.41, meaning that the impedance of the 2nd peak is 41% as strong as the impedance of the first peak. Generally, I find relative impedance easier to interpret and to read than “normal” impedance.

- note-number is a Didgelab-internal representation of the note. In general, A4 has note number 0. Ab4 is -1, A#4 is 1, and so on. Inside of Didgelab, this number is very important, outside not so much.

- cent-diff is the difference in tuning from the ground note. 100 Cent is one half-tone. As a rule of thumb, +-5 cent is a good tuning, +- 10 cent is a big off but acceptable and, above that, the tuning is bad. If the note is D1 and the cent-diff is 50, the tone is actually exactly half way between D1 and D#1.

- note-name Is the “normal” way to write a note number. So you can see that this didgeridoo has the first peak (ground tone) D1.

Lets interpret this resonant frequencies table: The ground note of that didge is D1 because it is the first peak. Sometimes you got another peak below the ground note, that is unplayable. In these cases, the ground note is the smallest peak that is larger than roughly 60Hz. Further, we can say that the Didgeridoo has toots D2, A3 and A4. The toot at F3 has a very low impedance (look at rel_imp here) and, therefore, is unplayable. Very experienced plays can maybe also play the toot at F4.

Sound spektrum

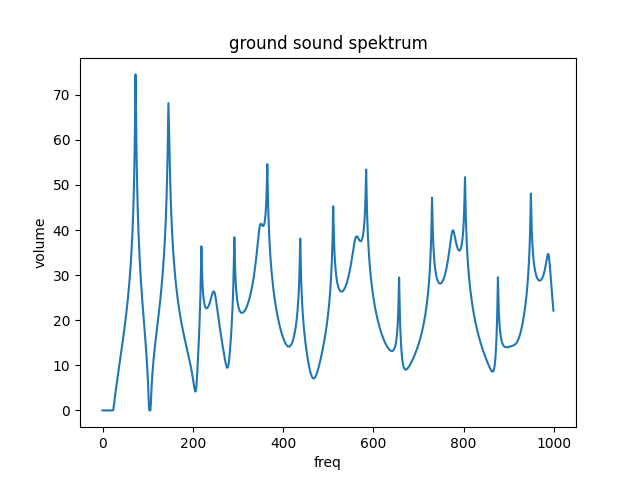

Impedance spektrum and resonant frequencies table show the toots of a didgeridoo. But they do not give a very good insight in how it sounds. Most people are mostly interested in the sound of the ground tone and maybe the first one or two toots. The sound spektrum is a visual representation of the sound. It is produced by an FFT analysis. Again, it is a spektrum over the frequency and shows how “loud” the sound is at each frequency. It is the same visualization that you see in an equalizer. I like to see it as the “tonal balance” of a sound. It shows if the sound is bright or bassy. Generally, you have a different sound spektrum for the ground tone and each toot. In Didgelab I usually print the sound spektrum of the ground tone, although it is possible to do the same for the toots as well.

Generally, I find it hard to deduct the sound of the didgeridoo from the sound spektrum because the sound spektra of bright or bassy didgeridoos look very similar. I would really like to start a project in which people rate didgeridoo sound examples on different scales (bright, bassy, earthy, clear, muffled…, whatever sound categories you can come up) and then we compute a transformation from the “technical” information, such as impedance or sound spektra, to these human readable scales: This didgeridoo is 80% bright, and has a 40% muffled sound. Hit me up if you would like to support that effort, it requires a solid data collection.